Reforming The Civil Service Examination By Ahmed S Cheema

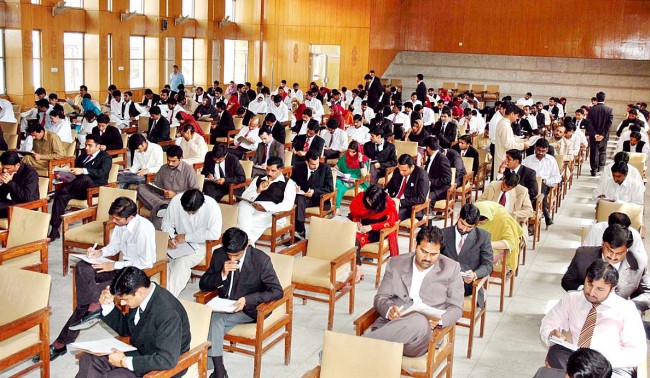

Every February, thousands of aspiring candidates take the Central Superior Services examinations administered by the Federal Public Service Commission (FPSC). In a week, they sit for a series of tough exams, often two per day. Of the 22,000 plus candidates who applied in 2020, barely 2.11 percent cleared the entire process. Candidates select 11 to 12 subjects with a cumulative 1200 marks. Six subjects are compulsory, specifically the English Essay, Precis & Composition, Current Affairs, Pakistan Affairs, Islamiyiat and General Science. Candidates select a further 5-6 optional subjects from a range of groups.

Pass these written exams, and you’ll qualify for subsequent stages, namely a psychiatric evaluation, group tasks and a final interview. Selected candidates go on to enter the hallowed halls of the Civil Service Academy – that bastion of enlightened and erudite bureaucrats who administer this country. As of now, there are 12 services or ‘groups’, i.e. the Pakistan Administrative Service, the Foreign Service, the Inland Revenue Service, the Audit & Account Group, the Customs Group, the Commerce & Trade Group, the Information Group, Police Service, Postal Group, Military Lands & Cantonments, Office Management Group and the Railways. Allocation to a specific branch depends on the total marks you achieve in the exam and interview. Score 800 marks or more and you may get allocated to a prestigious service such as the Foreign Service, while a lower score may result in being relegated to the Postal Group.

The Civil Service has often been described as the machinery that runs the state. If this is the case, it is vital that this ‘engine of the state’ is competent and efficient, capable of steering the country through the 21st century. Regrettably, this is far from the case. Some reasons behind the inefficiency of our civil services include the process through which candidates are examined, archaic training and the inability to adopt new management styles and emerging technologies. We must reform the exams and selection process to ensure that a qualified cadre of applicants administers the country.

In the future, AI and Data Analytics will play a greater role in the efficient delivery of government services, with civil servants utilizing AI programs and making data-driven decisions.

One challenge that the Federal Public Services Commission (FPSC) confronts is that of ‘ghost applicants’ and wasted exam resources i.e. candidates submit applications and the FPSC incurs the administrative costs of organizing examination facilities but these candidates never appear or give up halfway through the exams. It might come as a surprise to readers, but almost a quarter of candidates do not show up on the 3rd day, primarily because they feel that underperformance in an exam on Day 1 or 2 implies they probably will not get selected. Consequently, they deem it unnecessary to sit for any further exams. To deal with this and ensure that only serious applications are entertained, the FPSC can establish minimum academic criteria. For applications to be accepted, candidates would need certain grades in their O/A Levels, such as a minimum of 5 As in their O Levels and 1 A in their A-Levels with no failed subjects, or the equivalent in Matric/FSC Exams. Similarly, candidates would require a minimum Second Class in their University degrees. Failure to meet these prerequisite academic standards would result in the application being rejected. This would ensure that only scholastically capable candidates appear in the Civil Service Exams and academically challenged or non-serious applicants are weeded out beforehand, thus saving the FPSC millions of rupees.

The second problem the Civil Service faces is misallocation. Selected candidates might be suitable for certain specific postings but are allocated to a branch where they would not be able to perform to the best of their abilities. To ensure candidates are allocated to the branch where they would be suitable or where their strengths lay, we need to alter the process of examining candidates. The FPSC could divide the Civil Service Exam into two routes with a different set of exams, instead of a ‘one size fits all examination’ for all candidates. The first route would be the ‘Specialist Branch’ and the other could be the ‘Generalist Branch’. Candidates may submit an application for whichever route they choose. In the future, AI and Data Analytics will play a greater role in the efficient delivery of government services, with civil servants utilizing AI programs and making data-driven decisions. Knowledge of subjects such as Punjabi, Islamiyiat, US History or Gender Studies, while useful, is ultimately secondary and not a core competency that bureaucrats in these groups require.

Moving on, the FPSC needs to ensure that candidates have an opportunity to demonstrate their depth of knowledge, analytical skills and philosophical capabilities. During exams week, the FPSC could schedule one exam per day and ensure candidates perform to the best of their abilities, instead of overburdening candidates by conducting two exams in a day. In some rare cases, the academic quality of questions requires improvement and self-reflection on the part of the examiners. For instance, some questions in the Gender Studies paper in 2020 were badly articulated-expressed using substandard English, and most candidates couldn’t understand what the examiner was trying to ask. Furthermore, exams on subjects such as Political Science or International Relations end up becoming tests of writing speed instead of intellectual abilities. The exam paper on International Relations requires 4 essay answers, each at least 5-6 pages long, within 3 hours and 45 minutes. In comparison, international universities such as Oxford or the LSE expect their students to write an essay answer in 1 hour-giving candidates plenty of time to produce a comprehensive and analytical answer. After all, if we want to recruit someone as an ambassador, we ought to test them on their analytical and philosophical capabilities, instead of their writing speed. In some cases, candidates would obtain higher marks if their exam were more presentable e.g., they would use different combinations of blue and black ink on paragraphs to make these more presentable, or draw maps where none are needed – such as a map of Asia in questions on Pakistan-India relations. These are gimmicks that should have no bearing since factual and analytical knowledge should be tested. If examiners require graphs or tables, then the exam question should state these specifically.

Moving on, the academic standards of exams must be constant to ensure consistent quality. It is common to observe easy questions for subjects like Sociology and very difficult exams for Computer Science, with the result that applicants strategically pick subject combinations which are more likely to result in higher marks. Consequently, students tend to opt out of Economics and Computer Science even though knowledge of these subjects is vital for a modern Civil Service. The Civil Service ends up with candidates who have scored high marks on non-technical subjects such as Journalism and Punjabi, even though these subjects might not be as applicable to the qualitative performance of technically oriented government institutions eg Tax Departments. Likewise, the academic rigour of the exams tends to vary. For instance, subjects like Constitutional Law or European History might have easy exam questions in a specific year, resulting in candidates achieving high grades, followed by an extremely difficult exam the following year, resulting in very different results. This reduces our ability to examine the academic qualities of candidates across induction years. In contrast, an ‘A’ grade in your A-Levels Biology implies that you are likely to score an ‘A’ the following year since the examiners ensure standardized academic quality and difficulty levels. If the FPSC cannot ensure standardized quality and difficulty of examinations, it can outsource some examinations to professors and examiners who might be more suited to ensure that globally competitive academic standards are being met. Moreover, while reservations for candidates from backward areas could be continued in the ‘generalist’ branches such as the Police Service, reservations should be abolished for technical branches such as the Inland Revenue Service. Inductions in these technical branches ought to be based on strict academic merit since the performance of these branches has economic significance for the country.

Lastly, the training of each civil service branch can be enhanced to ensure that they specialize in their respective fields. For example, the Foreign Service Academy could increase its current training period by a year to ensure candidates study a Foreign Language, Grand Strategy, Public Diplomacy, International Law, and Economics, and are well-versed in new technologies that Pakistan requires. The Indian Foreign Service recently carried out reforms to ensure they have strong International Law and Science sections. Other government groups ought to improve their training by adopting new management techniques or absorbing emerging technologies. For instance, the Office Management Group’s training would include additional subjects such as Strategy & Management, Logistics and Data Analysis, while the training for the Postal Group could include Business Economics. This would ensure that civil servants possess technical skills and can make efficient data-driven decisions to benefit the public. As a result, these departments would function efficiently, similar to a multinational corporation, rather than a slow-paced lethargic bureaucracy.

The writer is a freelance columnist.

Reforming The Civil Service Examination By Ahmed S Cheema

Source: https://dailytimes.com.pk/1198189/reforming-the-civil-service-examination/