Why Biden’s Middle East Policies Look Like Trump’s By Paul R. Pillar

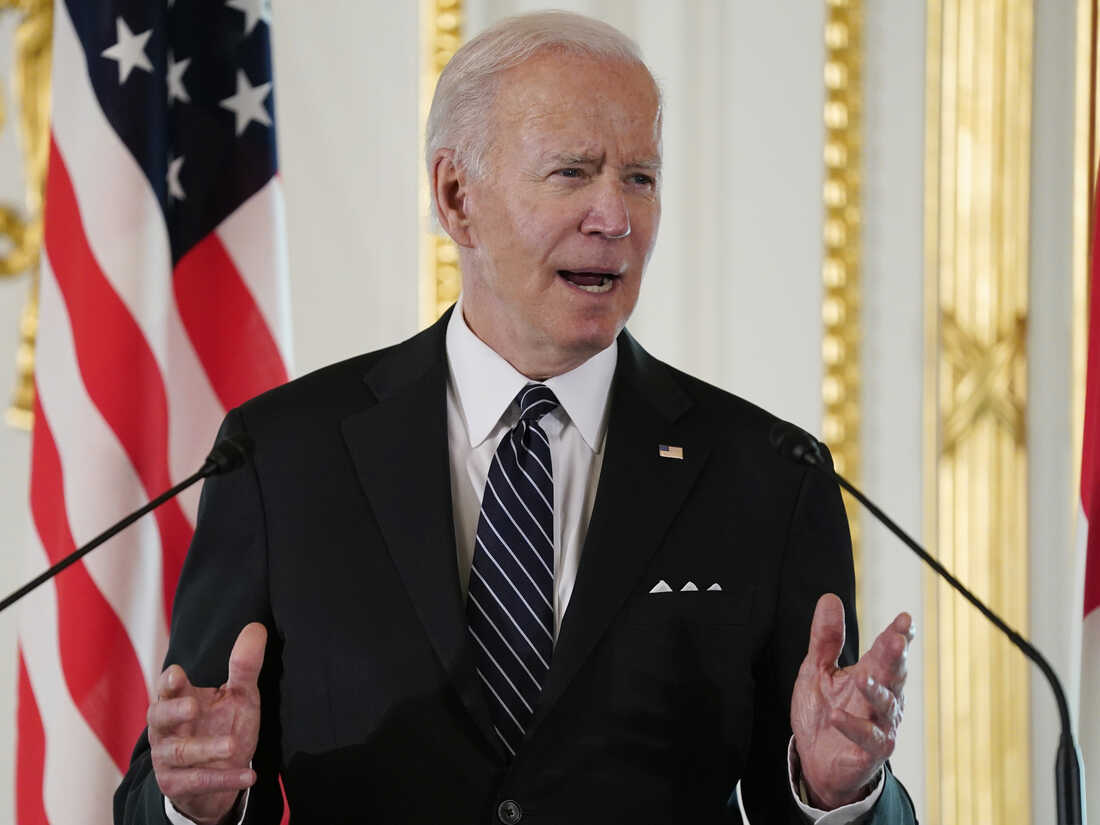

Joe Biden, who became the oldest U.S. president on the day he entered office, had a chance to become a very consequential one-termer. One-third of the way through his term, it is evident he is not taking that path. One indication, but not the only one, is that he reportedly wants to run for re-election. Age alone is sufficient reason this prospect gives Biden’s supporters pause. If Biden were to serve a full second term, he would be eighty-six at the end of it. For comparison, the next oldest U.S. president was Ronald Reagan, who was seventy-seven when he left office.

The biggest contribution Biden was destined to make to the nation was to restore integrity, truth, reason, comity, and a sense of public service to the White House after four years of Donald Trump. That contribution has been significant, although Biden needs to make more use of the presidential bully pulpit to impress upon the nation how imminent and severe the danger is of America losing its democracy altogether.

But a one-term president could be much more than that. A one-termer, not burdened with any of the hesitancies associated with seeking re-election, could break through old, stale, unproductive national habits in thinking about policy without fear of paying a personal political price. Such stale habits have marked some major aspects of U.S. foreign policy.

That Biden is not trying to break away from those habits is illustrated by his administration’s approach to the Middle East, as symbolized by his coming trip to Saudi Arabia and Israel. Insofar as a motivation for the mission to Saudi Arabia is toddle the Saudis to pump more oil, in order to lower both the price of gasoline and the associated discomfort of American consumers (and voters) about inflation, this is an example of traditionally narrow thinking that puts short-term domestic political considerations ahead of larger strategic matters. It’s not even clear there is much to gain from pressing the Saudis about levels of oil production.

Much commentary, pro and con, about the visit to Saudi Arabia has itself illustrated some stale thinking by oversimplifying the policy choice as one between treating the murderer of Jamal Khashoggi as a pariah versus talking to Saudi Arabia because it is a major player in Middle Eastern affairs. This kind of framing sounds like another old habit in discourse about foreign policy, which is to regard diplomatic dialogue as some kind of reward for good behavior, to be used only when we like what the people on the other side of the table are doing. Insofar as Biden’s administration has overcome this habit, that is good.

But the administration does not appear to have overcome the more fundamental problem in policy toward the Middle East of statically viewing the region as divided between good guys and bad, between allies and adversaries, without getting beyond those labels and paying sufficient attention to exactly who is doing what and how it affects regional security. The habitual static view depicts Israel and the Arab states that actively cooperate with it as the good guys, and Iran as the arch-bad guy.

A leading example of how that view does not accord with who is doing what—and how the United States can get dragged into messes created by regional players’ local ambitions—is the war in Yemen. Initially, a civil war triggered by tribal dissatisfaction over internal issues, the one factor that, more than any other, turned Yemen into a humanitarian disaster was the Saudi-led aerial assault on the country beginning in 2015. The United States, to its discredit, has aided this assault. The Biden administration, to its credit, announced last year that it was ending support to Saudi “offensive operations,” but U.S. indirect support to the Saudi air force continues in the form of maintenance and logistic help.

Yes, Biden has much to discuss with Saudi ruler Mohammed bin Salman, not just about the dismemberment of a U.S. resident and other human rights violations and certainly not just about pumping some more oil. The dialogue is necessary, but it should not be framed as a dialogue with an “ally” because it isn’t. Saudi Arabia is indeed a major regional player, and it has been a major regional troublemaker.

The next most destructive sustained aerial assault by a Middle Eastern state against a neighboring state is the Israeli air campaign in Syria. In addition to the direct damage and casualties from that campaign, it has heightened regional tensions and diminished any prospect of bringing peace to Syria. Here the Biden administration does not appear even to have executed the modest pullback it has with the Saudi air war in Yemen. Instead, the United States coordinates with Israel on the attacks, evidently for tactical deconfliction and not to address the illegality and destabilizing effects of the attacks.

The Biden administration’s inertia on Middle Eastern matters is further demonstrated by its falling in line behind its predecessor regarding the upgrading of relations between Israel and some Arab states (the so-called “Abraham Accords”). It even seems to be pushing Saudi Arabia to move in the same direction. It is doing so despite the fact that the upgrading has diminished, not improved, prospects for peace and stability by lowering any remaining Israeli incentive to make peace with the Palestinians and by intensifying tensions in the Persian Gulf region, in addition to other destabilizing effects (such as exacerbation of the Western Sahara conflict) from the side-payments the Trump regime made to induce Arab regimes to go along with the idea. Recently, the Israelis in effect acknowledged that the upgrading of relations has nothing to do with peace but instead is an anti-Iran military alliance.

Then there is the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the multilateral agreement that restricted Iran’s nuclear activities and that Biden genuinely wants to restore, but on which he has all but surrendered to some of Trump’s tactics for destroying it. Biden missed an opportunity to resurrect the agreement quickly by simply using executive action to undo what Trump had done through executive action and to bring the United States back into compliance with the JCPOA while the Iranian administration that negotiated the agreement was still in office. Instead, the Biden administration has continued most of Trump’s failed “maximum pressure” approach, which has seen a big expansion in Iran’s enrichment of uranium, along with no beneficial effect on Iran’s other regional conduct and the entrenchment of a more hardline Iranian leadership. The inertia of the Biden policy on Iran even includes not departing from the highly irregular Trump tactic of putting a branch of the Iranian military on a list intended to be for nonstate terrorist groups, a piece of inertia that has no practical benefit and reportedly has become the main stumbling block to restoring the JCPOA.

It is not too late for Biden in the next two years to shed this baggage and the domestic political fears that underlie it and instead embark on a fresh approach to the Middle East that cleanly follows U.S. interests rather than the objectives and conflicts of local actors. Not doing so would mean following the same tired old approach of the United States toward that region, an approach that has had more conspicuous failure than success.

Paul Pillar retired in 2005 from a twenty-eight-year career in the U.S. intelligence community, in which his last position was National Intelligence Officer for the Near East and South Asia. Earlier he served in a variety of analytical and managerial positions, including as chief of analytic units at the CIA covering portions of the Near East, the Persian Gulf, and South Asia. Professor Pillar also served in the National Intelligence Council as one of the original members of its Analytic Group. He is also a Contributing Editor for this publication.

Why Biden’s Middle East Policies Look Like Trump’s By Paul R. Pillar

Source: https://nationalinterest.org/blog/paul-pillar/why-biden%E2%80%99s-middle-east-policies-look-trump%E2%80%99s-203171